What are the directions of technical data platforms scalability?

- 6 minutes read - 1079 wordsTechnical scalability is one of the main drivers of a data platform, as mentioned in the SOFT methodology. But what are the options? In this blog we’ll evaluate the direction of scalability and the tradeoffs you might encounter in the decision process.

The main directions of technical scalability

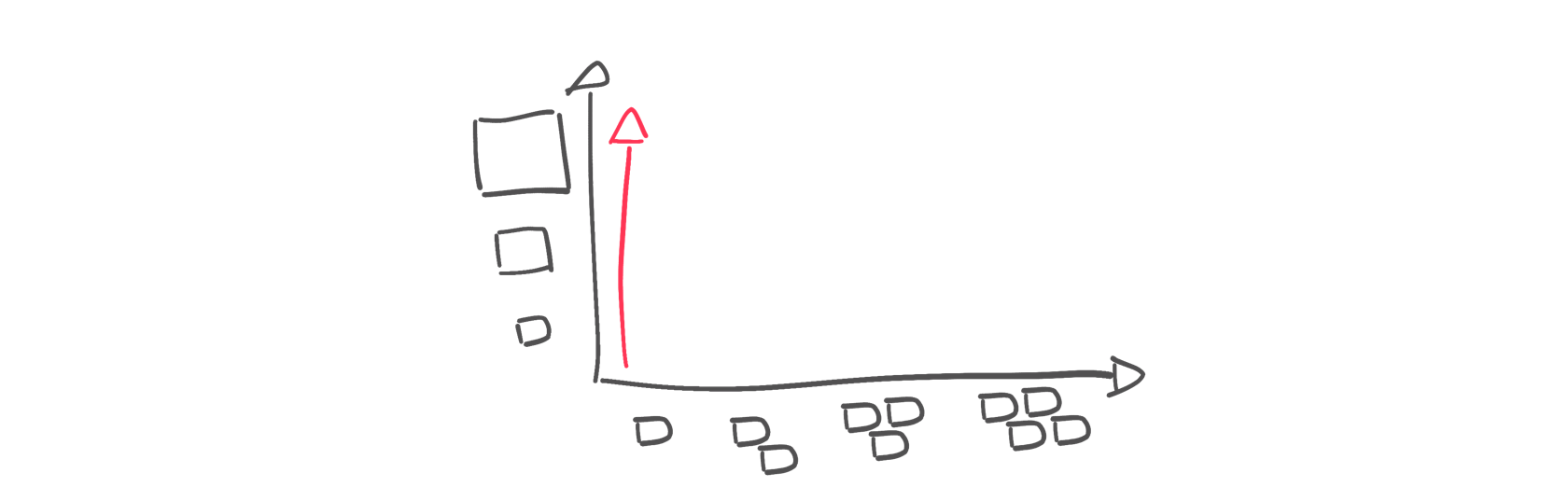

Vertical scalability

Vertical scalability generally means “buy a bigger box”: what can’t be achieved with a server sized X, could be achieved with a server sized 2X. There’s plenty of data platforms that allow this type of scaling and, with all the options available now in the cloud market, the vertical scalability can take you loooooooong way.

Pro:

- No changes in the architecture

- Easy estimation of new performance

Cons:

- Resource constraints on a single machine

- The cost of a single big machine is greater than the cost of more smaller machines

- The load is parallelized only within the machine

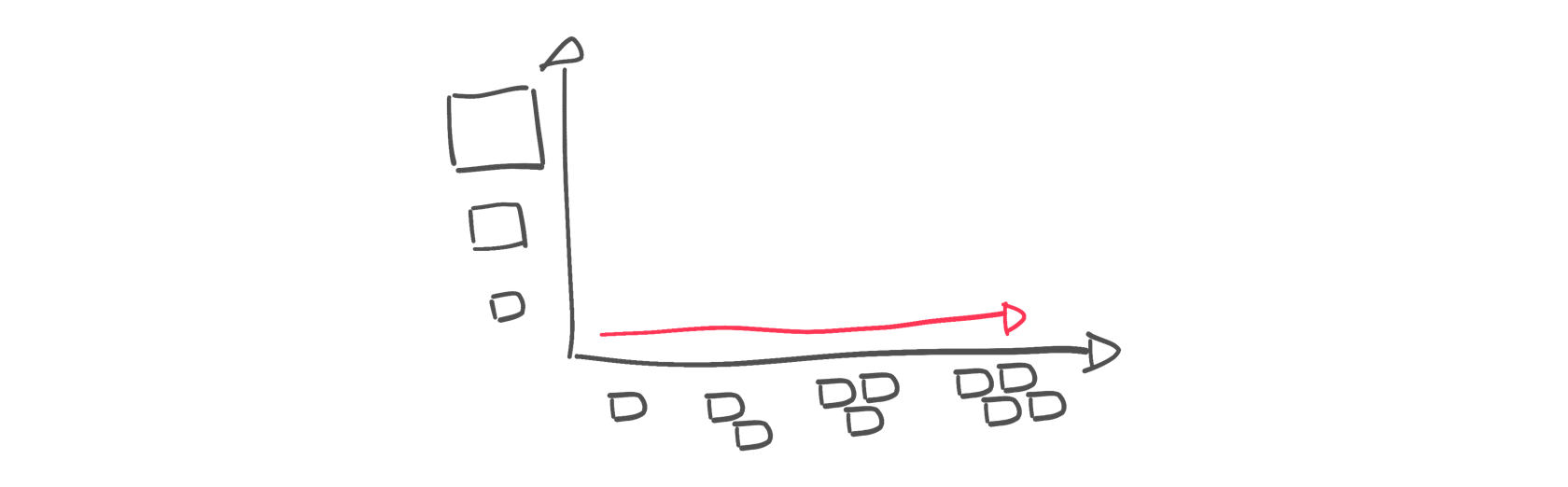

Horizontal scalability

Horizontal scalability goes on the opposite direction, instead of having a bigger machine, we spread the workload across several smaller machines. It’s usually available in distributed systems where the workload is shared across nodes. Apache Kafka is a perfect example: its distributed nature allows you to plug in and out nodes from the cluster and have an automatic rebalancing of the data and responsibilities across nodes.

Pro:

- Easy/Fast plug in of new resources

- Cost of more smaller machines is usually less of the cost of a single big machine

- The load is parallelized across the cluster

Cons:

- Only available in distributed systems

- Change in the cluster architecture for every new node added

- Data is replicated

- Might lead to eventual consistency

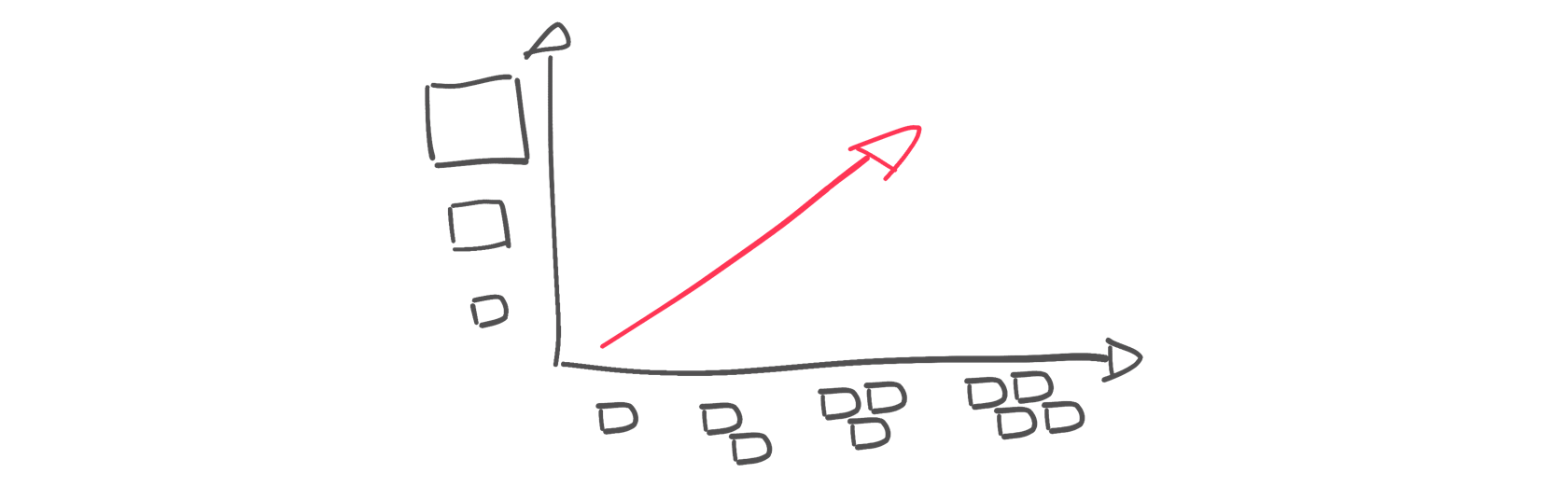

Diagonal scalability

A mix of the two, is of course possible, in situations where we could both add nodes to a cluster, and at the same time, replace the existing with new nodes of enhanced capacity. Typically the scenario is similar to the Horizontal scalability, the only change is that the new nodes have different (usually increased) specs compared to the previous ones.

Another way of scaling “diagonally” is to create different nodes for different purposes. Taking PostgreSQL as example, one might choose to scale vertically on the primary, but also scale horizontally to create one or more “read only replicas” that could fulfill all the read-only traffic, relieving the primary from part of the workload.

Pro:

- Freedom of scaling in both directions

Cons:

- Not always available

- For some of the technologies, the workload (e.g. write operations) can’t really be shared across all nodes

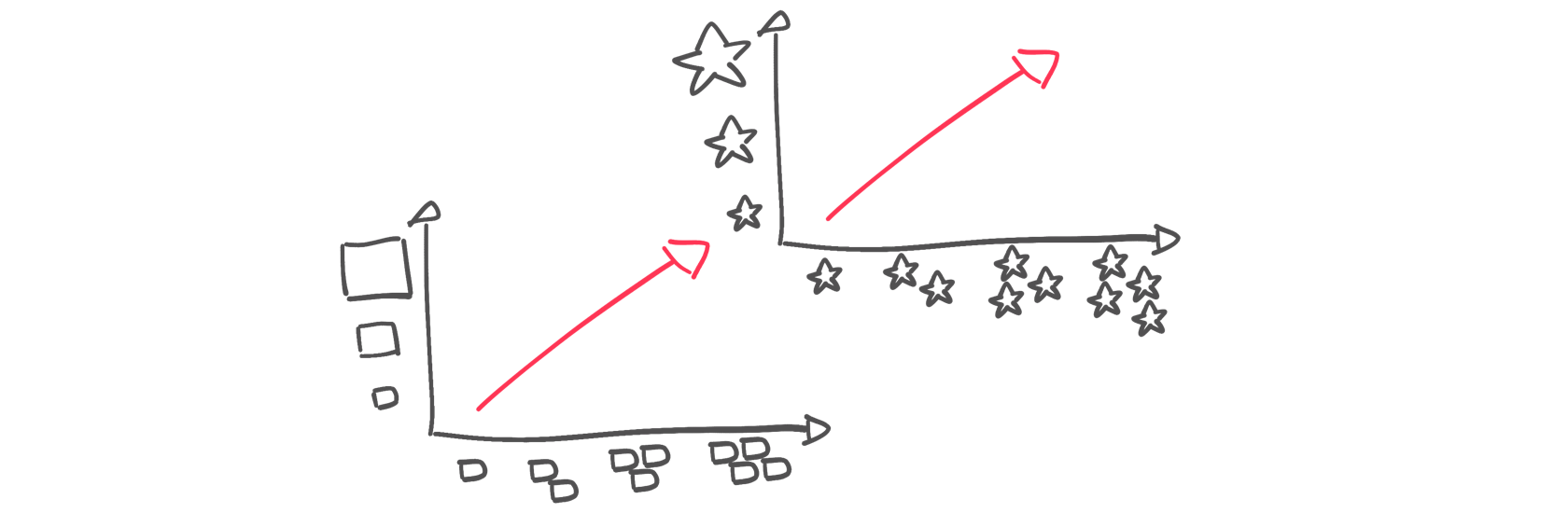

Cross tech scalability

Not all the workloads need to be performed in one single data technology: As the previous example with PostgreSQL read-only replicas, different nodes of a cluster can fulfil different workloads. Taking the example further, one could scale by storing the transactional data in PostgreSQL but then integrating ClickHouse for analytical workloads. This cross tech scalability allows to optimize each component for a single usage and scale independently.

Pro:

- Workload-optimised data platforms

- Independent, workload-related, scaling

Cons:

- Data synch between technologies

Challenges of data platform scaling

If data platform scaling was an easy task, we wouldn’t talk a lot about it. There are some challenges that the scaling operation brings with it.

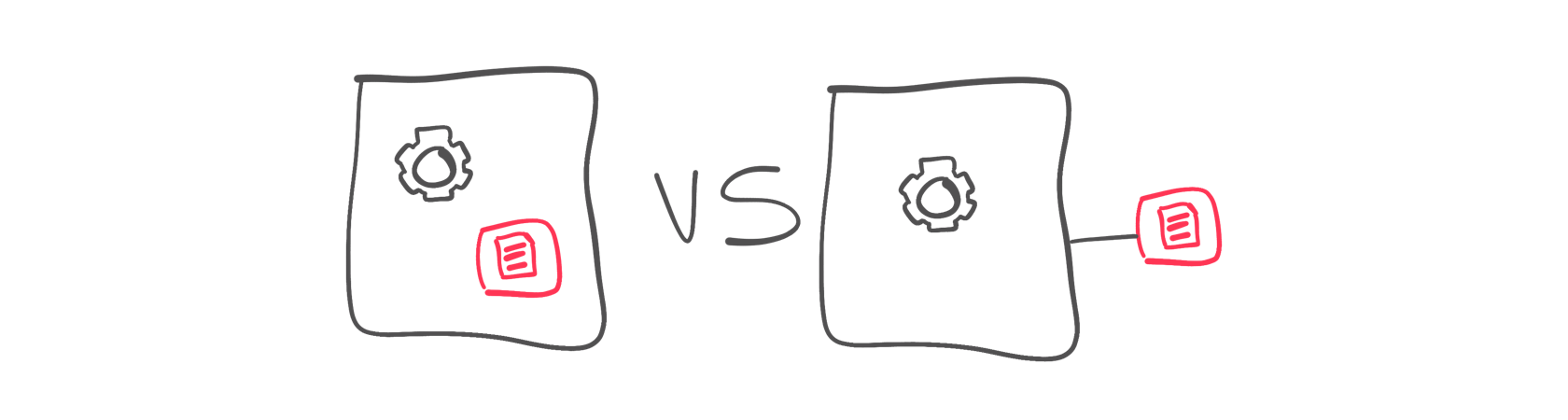

Where does the data reside?

To achieve optimal performance and minimize any network latency, data platforms historically stored co-located data storage and compute. In recent times, a new trend of detaching compute from storage (see Snowflake, neon) allowed further scalability options to increase the disk and the CPU independently at the cost of (a small) additional latency. The tradeoff is between performance (immediate local access), workload isolation/independent scaling.

Furthermore, if the data is co-located with the compute, it needs to be moved when performing, for example, a vertical scaling.

Check this youtube video from Gwen Shapira to understand more

Time to scale

Depending on the architecture, the time to scale can vary between fractions of a second (in case only a new compute instance needs to be spun up) to hours (in case huge backups need to be restored). Evaluating the time to scale is necessary to understand the scaling thresholds: e.g. if one can scale in 10 seconds, the scaling option could be triggered at 95% capacity, if the scaling takes a few hours, the threshold needs to be lowered.

Downtime

Nobody wants downtime, specifically when needing to scale up to follow a rise in demand. However one must understand and evaluate:

- how much work can be done without changes in the original system

- how long is the switchover downtime (if any)

- how and how fast clients can re-sync connection parameters

Answering the above queries will help understand how to minimize the unavailability of the system.

Scaling-induced additional load

The scaling operation might induce additional load on the system, e.g. when streaming changes from one node to the other. Evaluating how the additional load could impact system performances needs to be done upfront to ensure to provide a sufficient service during the scaling procedure.

Not all workloads are equal

As mentioned before, the type of scaling depends on the architectures and workloads: adding a read-only replica in a specific cloud region is a fairly low cost solution to alleviate some load from a primary PostgreSQL database. That said, the solution doesn’t work when a lot of write workloads are in the game.

Backups/Restore

What does it have to do “backup/restore” with scaling? Well, some of the technologies (hi PostgreSQL!) will initially restore a database copy from a backup and then start streaming the delta from the primary. Therefore, in such cases, having a ready to go, and up to date backup allows you to cut the time to scale.

More data jumps more risks

In some of the scenarios presented above, scaling is performed by adding new nodes to a cluster, or adding new technologies in the mix. Even if these options provide great benefit in the parallelism and the separation of workloads they are adding additional steps in the data journey.

Every time there’s more than one server storing the data, there’s always the chance of not-in-sync replicas. Every time you add a new data hop, there are always additional complexities with network, integration, etc.

Conclusion

This article aims at covering a wide spectrum of scaling possibilities and related issues. When designing a data platform, the scalability problem (not only technical, check out the SOFT methodology to know more) should be an important decision factor to evaluate a solution based on the underline technologies, the expected workloads and the business constraints.